“The Guitar That Shaped a Generation: How Mark Knopfler’s Les Paul Defined Brothers In Arms

Dec. 20, 2025, 9:15 a.m.

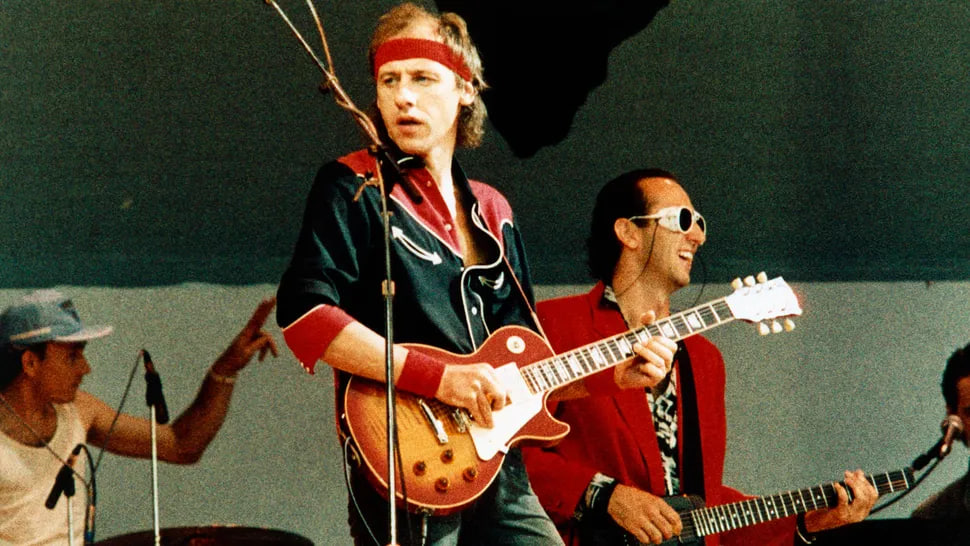

Mark Knopfler today prefers to keep Brothers In Arms at arm’s length. Dire Straits’ monumental fifth album feels like a relic from another lifetime — a creation of the red-headbanded guitar slinger he once was, a version of himself the 76-year-old barely recognises now.

Before retiring from touring six years ago, Knopfler would occasionally revive a tune or two on solo stages — such as a triumphant Money For Nothing in Madison Square Garden in 2019. But the album itself? He rarely discusses it and never enjoyed the spotlight it brought.

In an interview back in 1995, he downplayed its enormous success:

“The album just happened to arrive when CDs exploded. Pure coincidence. If not this one, another record would have blown up. It was timing, nothing more…”

He’s been so silent about Brothers In Arms — and so firm about never reuniting Dire Straits — that some younger music fans have grown up without even hearing about the 30-million-selling giant.

But anniversaries have a way of opening old doors. For the 40th anniversary, a lavish reissue appeared this year, including the iconic National resonator artwork and a blistering live show from San Antonio.

Even more surprising: Knopfler, bassist John Illsley, and several longtime collaborators agreed to speak at British Grove Studios — a rare gesture. On a warm afternoon in West London, we find Knopfler in Studio 2, quietly sipping an espresso behind thick-rimmed glasses.

A hesitant beginning

He starts carefully, but a guitarist’s in-joke about the impossibility of playing in a chair with armrests breaks the ice, and suddenly the years melt away.

“It’s tempting to shrug and say, ‘Oh, nothing special,’ but looking back now, that record clearly meant a great deal to a great many people.”

Illsley recalls the early stages: a small mews house in Holland Park, the band gathered in tight quarters — Mark, John, Alan Clark, Guy Fletcher, and drummer Terry Williams beating rhythms on a cardboard box.

Songs varied widely: the levity of Walk Of Life balanced the solemnity of Brothers In Arms. Illsley mostly shaped his bass lines around Knopfler’s thumb-picked low-string patterns — a habit reaching back to the first Dire Straits album.

A spectrum of styles

The musical palette was unusually broad:

-

So Far Away blended warm groove with futuristic Synclavier textures.

-

Your Latest Trick evoked smoky film noir.

-

Walk Of Life mixed rockabilly swagger and zydeco-like hooks.

-

Brothers In Arms and Money For Nothing stood as towering pillars.

Knopfler describes the latter’s riff:

“It’s basically a stomp — a two-fingered boogie. I was listening to ZZ Top a lot. The trick is muting everything you don’t want to hear.”

Illsley insists:

“People think anyone can play it. But very few can play it the way Mark does.”

The four sacred notes

Live, Knopfler almost never replicated studio parts exactly — except the opening of Brothers In Arms.

“Those first four notes are like furniture in the room. If you change them, the audience knows instantly something’s wrong.”

Yet each verse of the song subtly shifts from the previous one — microscopic adjustments that change the emotional color. Many classically trained players miss these nuances.

Montserrat: paradise under storms

The band booked AIR Studios on Montserrat for winter 1984. It turned into a rain-soaked marathon that frustrated producer Neil Dorfsman, who complained that progress was slow and the guitar tones “too dark.”

During this period, Knopfler barely touched his famous Fender Stratocaster ’61. Guitar tech Ron Eve recalls:

“He took it out once or twice, but he had other instruments that fit the new material better. That Stratocaster was almost a partscaster — he found it limiting.”

Enter the hero: Gibson Les Paul ’59 Reissue

This album marked the true arrival of Knopfler’s now-legendary Gibson Les Paul ’59 reissue.

Eve explains:

“We found it at Rudy’s Music in New York. The neck was perfect — not too thin, not too fat — and the sound was stunning.”

He even rewired it himself for out-of-phase tones reminiscent of Peter Green — without asking Mark.

This Les Paul provided the thick, singing voice of Brothers In Arms and the punch of Money For Nothing.

Illsley summarises:

“A Stratocaster is like a ballet dancer. A Les Paul carries emotional weight. It was the only guitar that could speak for that song.”

And Eve admits:

“I nudged him toward that sound — and it paid off.”

But other guitars had their moments

Not every track called for the same instrument:

-

Walk Of Life used Knopfler’s 1983 Schecter Tele-style guitar for its chunky twang.

-

The Man’s Too Strong showcased the resonant metallic voice of the National guitar.

-

Rumors about a Les Paul Junior on Money For Nothing? Pure fiction.

Amps, pedals, and the synth-guitar experiment

The signal chain was simple:

-

Eve’s Marshall JTM45 (inspired by the Bluesbreakers),

-

Laney 4x12 cabinet,

-

and a single pedal — a Cry Baby wah for Money For Nothing.

The oddest piece of gear wasn’t used by Knopfler at all: a Roland synth-guitar. It simply couldn’t interpret his feather-light touch, so session guitarist Jack Sonni performed those parts.

The master’s humility

Sitting across from one of the greatest British guitarists alive, you don’t expect to hear self-criticism — yet Knopfler is blunt:

“I gave up trying to be a ‘great guitarist.’ I’m just someone who plays well enough to record the songs I write.”

He recalls how long it took to understand timing, after years of engineers telling him, “You’re rushing.”

The tour and its cost

Released in May 1985, the album was everywhere. The tour that followed was exhilarating — and exhausting.

Illsley reflects:

“It felt magical. But tough. Mark took the brunt of the fame. You can’t get coffee without someone staring.”

Knopfler never liked the celebrity aspect:

“Someone once yelled, ‘You’re top, man!’ in Manchester. But I never felt on top of anything. Not then, not ever.”

Final thoughts

When asked if he ever listens to Brothers In Arms, Knopfler reacts instantly:

“Never. Why would I go home and play my own records? Life’s tragic enough…”